In the age of digital payments, CEO Dan Schulman kept the company relevant by teaming up with its foes. “It took us 14 years to go from 50 million subscribers to 250 million,” Schulman says. “I mean, it’s impressive, but it’s a long time. We went from 200 million to 250 million in about 18 months,” tripling the rate at which the company added users, or what it calls “net new actives.” PayPal’s stock is up more than 100 percent since the start of 2017. However, PayPal’s most impressive statistic may be its conversion rate. People who design online and mobile shopping apps are obsessed with smoothing and shortening the path from idle browsing to purchase—humans are acquisitive and impulsive creatures, but they’re also easily distracted and bad at remembering their credit card numbers. Too many options hurts conversion, and so does having to type out stuff or wait for a page to load. PayPal’s conversion rate is lights-out: Eighty-nine percent of the time a customer gets to its checkout page, he makes the purchase. For other online credit and debit card transactions, that number sits at about 50 percent.

By Drake Bennett and Julie Verhage

Bloomberg Businessweek

January 8, 2019, 3:30 PM GMT+5:30

PayPal Quietly Took Over the Checkout Button

In the age of digital payments, CEO Dan Schulman kept the company relevant by teaming up with its foes.

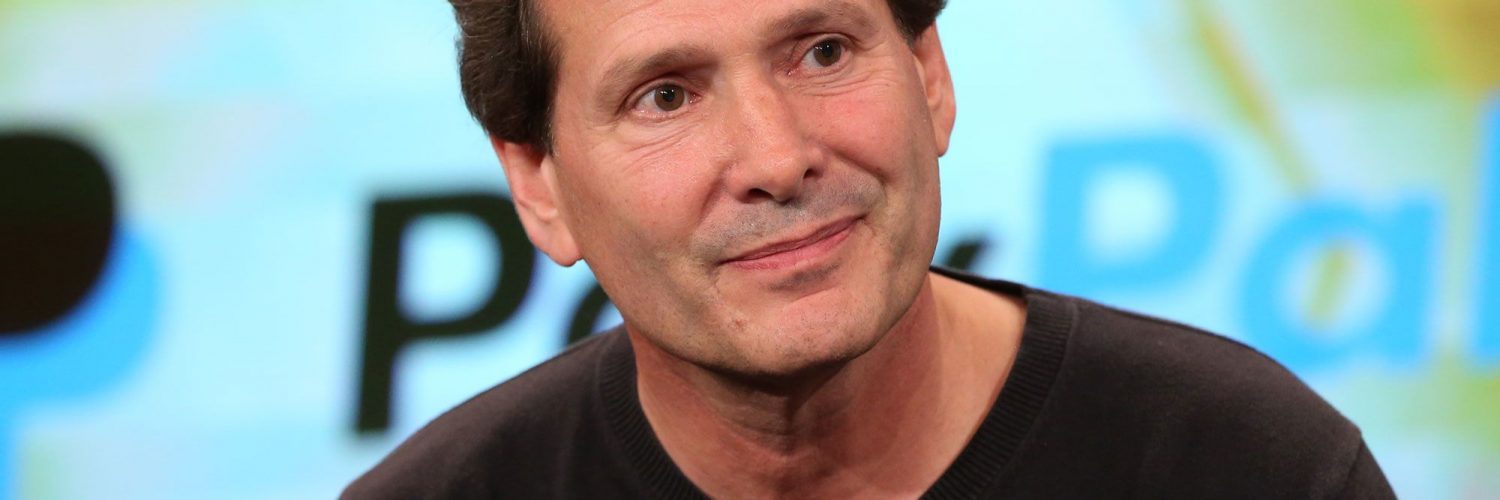

Dan Schulman, chief executive officer of PayPal. PHOTOGRAPHER: ULYSSES ORTEGA FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

In late 1999 a young computer scientist named Max Levchin started receiving emails from strangers about a web demo he’d created to illustrate the workings of an app. The app, which he’d also helped create, was an encrypted payments platform for the state-of-the-art mobile device of the day, the Palm Pilot: Two users would agree to the transaction, the sender would enter his credit card number into his device, and once both Palm Pilots were physically plugged into their owners’ computers, the appropriate amount would be debited from one and credited to the other. “It was fairly clunky,” Levchin concedes, “but it was a full-loop way of transferring money.” The app was the fourth or fifth pivot for his startup, and it grew out of conversations with another co-founder, a lawyer and venture capitalist named Peter Thiel, with input from a board member named Reid Hoffman. They decided to call the app PayPal.

Because most people didn’t own a Palm Pilot, Levchin also created an online simulation of the app that allowed someone sitting at a computer to enter financial information and actually send someone else money. “I thought of it as, ‘If you’re deciding whether to get a Palm Pilot, here’s one way of enticing you,’ ” Levchin says.

But the people emailing him had no interest in Palm Pilots. They wanted to buy and sell stuff on the internet. EBay sellers had happened upon the demo and noticed that, in mimicking the Palm-to-Palm transfer, Levchin had incidentally created a working web payment tool. At the time, EBay payments were still checks in the mail, but if EBayers included a link to Levchin’s demo in their auction pages, they could pay one another instantly with a mouse click.

Levchin wanted nothing to do with it. To him, “e-commerce,” as people were starting to call it, seemed both silly and dangerous. “I felt that there was too much fraud taking place on EBay—and frivolous purchases. People selling Pez dispensers to each other,” he says. “That’s just not the business I wanted to be in.” He ignored the emails.

Fortunately for him, Levchin was fighting a losing battle. Thanks to the internet, collectors and hobbyists all over the world could now find one another to traffic in rare toys, first editions, and other esoteric objects of desire. Levchin’s demo was the first reliable, speedy way to settle transactions in this exploding global cyberbazaar. The sellers started linking to his demo without his permission. When he resorted to sabotage, blocking the PayPal logo from loading, they simply took a screenshot and embedded that. It was only a matter of time before the demo became PayPal’s actual product.

“At some point I sort of quit trying to stop the EBay users and mostly focused on figuring out how to not lose money,” Levchin recalls. When PayPal Holdings Inc. went public in 2002, it was processing 295,000 payments per day, worth $16.2 million. It pioneered identity verification measures and provided recourse for buyers and sellers who got scammed. The brand became synonymous with online payments far beyond the world of candy dispenser obsessives.

ts reputation, however, was also hitched to that of EBay, which purchased the payment processor months after its initial public offering. As a result, PayPal’s image has been fixed in a sort of early-internet amber. The company remains better known for the subsequent adventures and misadventures of the men who started it, all of whom have since left. Levchin is a venture capitalist and runs an installment payments startup called Affirm. Along with him, Thiel, and Hoffman, the so-called PayPal Mafia includes Elon Musk, who merged his financial-services startup with theirs in 2000. And yet, though a product of the bygone era of the Palm and the first internet boom, PayPal has managed to grow, acquire, and negotiate itself into a position as one of the biggest players in global payments. Now independent of EBay, PayPal has a market capitalization of $100 billion, 100 times what it was worth when it went public in 2002, and the number of users has grown from 15 million to almost 250 million. While it’s struggled in China, where WeChat dominates payments, in the rest of the world it processes as much as 30 percent of all e-commerce transactions, according to some estimates.

And digital payments are far bigger than they were when e-commerce meant EBay auctions—globally, shoppers spent almost $3 trillion online last year. Today there are smartphone “wallets,” online-only banks, and iPad cash registers. PayPal plays a role in all of them. It owns Venmo, the “social payments” app, and Xoom Corp., a digital money transfer service used to send money abroad. It processes payments for Uber. It even offers small-business loans. The company’s ambition, Chief Executive Officer Dan Schulman intones, is to be “the operating system for digital commerce.”

There are others with that same ambition—large, powerful corporations competing to extract a few fractions of a cent from the thousands of transactions flying around every second. It’s not only financial companies such as Visa and JPMorgan Chase, but tech Goliaths including Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Google. Chinese giants Alibaba and Tencent are also eyeing this market. PayPal is thriving in this tricky environment because it’s managed to reinvent itself as much more than just an internet checkout button: It’s a partner to tech companies eager to move into finance and financial institutions eager to move online. As much as any other company, PayPal has helped create a world where people feel increasingly comfortable spending their money in anonymous online transactions.

In the late 2000s, almost a decade after it first went public, PayPal was drifting toward obsolescence and consistently alienating the small businesses that paid it to handle their online checkout. Much of the company’s code was being written offshore to cut costs, and the best programmers and designers had fled the company. The result was a slow site whose rickety infrastructure made updates and new features laborious and rare. Companies that would otherwise have leapt to incorporate the PayPal button on their sites despaired of figuring out how to work with its technology. To make matters worse, PayPal’s heavy-handed approach to fraud prevention meant that it routinely declined legitimate payments, costing its merchant customers business. And its customer service could be Kafkaesque: In one notorious incident, an EBay seller reported that a buyer who’d disputed the authenticity of an antique violin she’d sold him was instructed by PayPal to destroy the instrument to get his refund—he did, sending photos of the shards.

The turnaround started with David Marcus, a French-born entrepreneur who came to EBay when it bought his mobile payments startup in 2011. He’d been there less than a year when he was asked to run PayPal, and he quickly set about rebuilding the software platform, replenishing the ranks of programming talent, and softening the corporate persnicketiness about disputes and suspicious transactions. He invited customers to tweet their complaints at him. He also began to push the digital payments processor into new markets. He oversaw the development of PayPal Here, which uses a plastic card reader that plugs into phones and tablets, turning them into digital cash registers. (The idea was pioneered by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s other company, Square Inc.)